Interview: Jillian Billard

All Images and Video Courtesy of the Artist

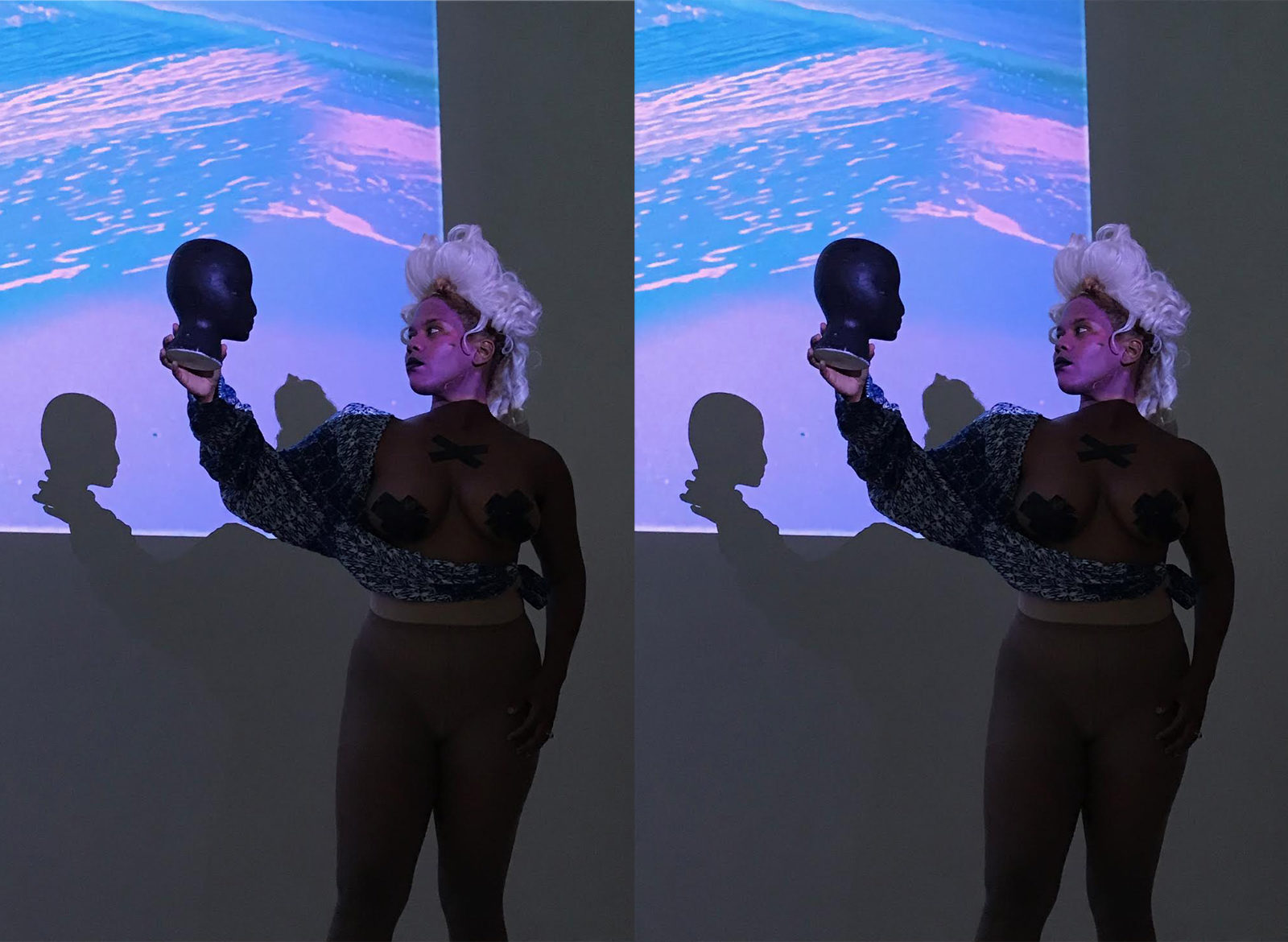

Performance artist Samantha CC’s practice is deeply rooted in self-discovery. The New York-based artist’s most recent performance work, Fragmentina’s Motherland, is a riveting allegorical expression of what it means to be black in America. Growing up in a predominantly white neighborhood in Brooklyn Heights, Samantha has long felt disconnected from her historical roots. Fragmentina’s Motherland is an expression and a reconciliation of this feeling of being forced to adopt an identity that is not her own. The character of Fragmentina washes up on an unknown shore and cannot remember where she came from, she only knows that she was taken from her home against her will. She is surrounded by objects that are unfamiliar––driftwood, an array of dolls, an American flag, a colonial wig. She begins to interact with these objects in an attempt to piece together her identity. She attempts to build a ship and navigate home, however it soon becomes apparent that she may not have a home. Through this character, Samantha navigates her own feelings of displacement and her attempts to piece together an identity that is, at its core, fragmented. We spoke to Samantha about exploring her lived experience through this character; the black American community’s burden of continually reconciling with the trauma of the Transatlantic slave trade; and why there needs to be more discussion around performance art.

I thought we’d start by discussing your background, as it’s so integral to your work. Can you talk a bit about your early life and how you came to performance?

I grew up in Brooklyn Heights. My mom grew up in Harlem, and my dad grew up in Tacoma, Washington. Both of my parents grew up in predominantly black neighborhoods, whereas Brooklyn Heights is a very white neighborhood. As I’ve gotten older I’ve come to realize that I’ve felt alienated for most of my life because I grew up in these predominantly white spaces. In a way, this experience has brought me to performance.

There’s this term that’s popular right now, which is “black respectability politics.” I feel like that was a tenet on both sides of my family. My grandfather on my mother’s side was a doctor, and both of my grandmothers were teachers, which back then was pretty much the most “professional” job that a black woman could have. These days, “black respectability politics” is often discussed with a negative connotation, as it tends to be associated with an elitism that causes division within the black community. However, during this time of rampant discrimination, segregation, and violent racism, I think a lot of black people felt that if they acted a certain way, they would be immune to the more horrific aspects of racism. It was a means of survival. Right now there is a lot of energy being put towards unpacking and challenging black respectability politics. This may seem like a tangent, but I think these aspects of my background inform a lot of my work.

How has performance acted as a way for you to explore your identity and reconcile with these formative experiences?

I like performance because it’s a bodily art. You use your body like you would language. I’m full of feelings and ideas that are hard to express with words. The Fragmentina’s Motherland performance really touches on and is inspired by my background and my experience as a black woman with my specific upbringing.

How long have you been working on Fragmentina’s Motherland, and how did it come to fruition? I’d imagine that these are ideas that you’ve been working with for quite some time.

I developed the idea for Fragmentina’s character relatively recently––I think I started working on it around April. But the ideas that are behind it have been with me my whole life, particularly the past few years. For me, the practice of making art is the process of turning my thoughts into poetic form. Alternatively, sometimes you can have this poetic image that comes to you out of the ether, and when you explore that image through your work something concrete starts to emerge. In the case of this performance I thought of the name Fragmentina first, and then everything came together after that.

Do you think that abstracting these thoughts that you’ve been considering for a long time and making them into something poetic helps you to delve deeper into it?

Yeah, I think it does, in a way. It’s more making the ideas into a myth or an allegory. I’m definitely referencing the post-middle-passage experience but I’m not specifically talking about that either––I think the allegory is more about someone like me who is a few generations removed from slavery. I guess I’m only one generation removed from segregation. The ramifications of all of these things are still very much with us. Essentially, I’m trying to piece together an identity based on all of these different signifiers that have influenced me as a child going through this individuation process.

With black culture, there’s what people refer to as “the culture,” which is basically any sort of art form or practice that is traditionally associated with African Americans. It refers to anything from music, to food, or doing the electric slide at parties. I definitely have a familiarity with a lot of these things from my upbringing, growing up in Brooklyn Heights I had a lot of white Jewish friends and classmates, so I also have a lot of these other reference points that also feel very much like they’re a part of me. I have maintained a lot of close friends from my childhood, but on a level of cultural connection I’ve always felt this disconnect, even with people that I have a strong interpersonal bond with. I’ve never really had the feeling of being an insider in any cultural space. I relate to most black women because we have a lot of shared experiences, but on a cultural level, I don’t know that I really relate to much of anyone very well.

You mentioned translating your experience into a form of allegory. Can you elaborate a bit on this, and your interest in themes of the divine? Do you think that mythologizing a lived experience can make it more accessible, not just to an audience but also to yourself?

I became a very spiritual person in my mid-20’s while recovering from a very traumatic period in my life. It really helped me to heal and think about myself differently. It’s still important to me but I also have become increasingly critical––especially with the rise of internet meme culture––of the way that spirituality gets communicated and simplified. I think there’s a lot of spiritual bypassing that gets encouraged by these platforms that can be problematic. Like, for example, I’ve seen these memes that say that “you’re not responsible for anyone else’s feelings,” and I can see how that could be helpful for people who are empaths and who really absorb everything that’s going on around them, but I think abusive people can and often do appropriate these sentiments to justify a lack of empathy. Accountability is so important! So I think that the messages just get lost a lot. Spirituality and the divine are important elements in my work, but I want to try and figure out a way of talking about or manifesting it that leaves a lot of room for emotional ambiguity. It isn’t just about leaving pain behind, but rather it’s about thinking about pain and challenging experiences in a more holistic way.

I've never really had the feeling of being an insider in any cultural space.

You’ve spoken in the past about performance being a path from pain to a sense of peace. Would you say that this piece works in this way?

That was how I used to frame my work, but I’ve kind of moved away from that. Of course peace is always something to strive for, but I think that we’re at this point right now where we can’t be complacent. We really have to keep our eye on the world right now––not just floating above it. Otherwise you’ll look down and everything will have eroded. There’s always a question of how much an individual can really do to change things, but I do think there are small things that we can do in our immediate communities––for our neighbors and just in terms of how we interact with authority––that do make a collective cultural difference.

I do think that you have to reach a place of peace within yourself in order to be able to fight those battles. For me that’s more about developing confidence and inner strength.

For a long time it was hard for me to make art, because I just didn’t have the confidence. There was always this voice that was like “who cares what I have to say?” I think when you get to a point of peace with yourself you don’t have to worry about whether or not you’re saying the “right” thing. What you, or I, or anyone has to say is important in terms of finding a collective truth, or deepening understanding of our world. So that’s what “peace” means for me––this ability to stand comfortably within yourself and add your voice to a greater whole.

Performance seems to revolve a lot around community, particularly in New York. Is this something that you’ve experienced in coming to the medium?

I began working in my current mode of performance after working with choreographer Monica Mirabile. She’s in a duo called Fluct with another performer, Sigrid Lauren. For a while Monica was doing these big ensemble pieces and would often have open calls. I did a few of those pieces with her and I really loved it. This was a community where queer people, femmes, and people of color were really empowered. There are also all of these great spaces that revolve around that community––Otion Front is one of them, as well as Secret Project Robot.

I’m actually always becoming familiar with new performance communities––just last night I met some people who are associated with Grace Exhibition Space and Panoply Projects. I’m actually participating in an ongoing performance forum at Panoply currently. So there is a lot of community around performance right now. I think we’re in a pretty exciting moment.

Along those same lines of fostering community––could you talk a bit about your publication project, The Great Black Expanse?

The Great Black Expanse is a couple of things––we put out a zine and it’s also a showcase for performance and video art––which I obviously chose because those are the mediums I work in (laughs). So far we’ve put out two zines and have had a few shows. I started that project because I was meeting a lot of performers from the African diaspora who weren’t necessarily doing similar work to me but were creating work in the same general sphere. I wanted to start a showcase to bring us all together and form community.

I wouldn’t say that the project is finished, but recently I’ve been more focused on cultivating my own practice. I also want to figure out a new way to approach the project. I got to a point where I realized that if I was going to put on shows, I wanted to find a way to offer artists some sort of honorarium or compensation for their work. Especially with black artists, there’s often this issue of just not getting properly compensated for things. Realistically, any amount of money that I would be able to give, unless I get some mega-grant, is just not going to be so substantial. Artists put a lot of time and resources into putting a show together and I don’t want artists to lose money being in my shows. A lot of times, even when I get paid for shows now, I usually just break even. I have mixed feelings about this, because there are so many people who have really important curatorial visions but they can’t afford to pay someone or don’t necessarily have the education or background that would make it easy for them to write a grant. It just gets so political and there are so many factors that are outside of your control. So I don’t necessarily think that people who aren’t able to pay artists shouldn’t be able to put on shows, but I do think there are other things you can do to make up for that. Like, if you can figure out how to get really good documentation of a performance, for me that means a lot. It could just be as simple as promoting the show really well. I do think that curators should be thinking in that way––you know––about what artists are sacrificing to make their work. People are willing to put so much more work and energy into the pieces if they feel like they are being respected and supported.

Since I started The Great Black Expanse I’ve rethought a lot of the things that were the original onus behind it. Representation and inclusivity are still incredibly important, but black artists are getting a lot of significant recognition right now in the art world and I think that things are really starting to change in that regard. Up until pretty recently if felt like there was a black art world, and then there was what’s called “the art world” which is mostly white. That dynamic seems to be shifting––with things like the sale of that Kerry James Marshall painting recently.

I called my project “The Great Black Expanse,” but recently I’ve seen people curate shows that only feature artists of color or only feature queer artists, but the way that the event is described and promoted doesn’t frame it around those identities. They’re just artists, not “queer artists” or “black artists.” I think that’s a really interesting approach because it evades the tokenization element.

What you, or I, or anyone has to say is important in terms of finding a collective truth, or deepening understanding of our world. So that's what ‘peace’ means for me––this ability to stand comfortably within yourself and add your voice to a greater whole.

Fragmentina’s Motherland explores this sense of displacement, not just of black artists but of black culture in general. Could you talk a bit about how the performance came together and your experience of it?

I was thinking about the formation of culture in the wake of something like the Transatlantic Slave Trade, where you’re ripped away from your culture of origin and brought into this space that is oppressive, and your history from there on out, over the course of generations and whether you like it or not, is partially defined by colonialism and that moment. People refer to it as America’s original sin. I think that’s a good description.

Right now, with the release of Black Panther, there’s all of this fantasy about Wakanda and Africa as this Utopia. I do think that’s really beautiful and I do relate to it in a way. I took a DNA test recently and found out that I’m something like 57% Nigerian, so I would love to go to Nigeria––I’m sure I would see a lot of people walking around there who look like me––however on the rest of the DNA test I’m like 25% British and a couple of other nationalities. I just think that you can’t really erase that from your history. I think it’s dangerous to fantasize about Africa as this pure land that you go back to and have this huge awakening homecoming experience. Africa wasn’t just frozen in time for us to one day go “back” to. I know some people do have a revelatory homecoming experience and it’s beautiful for them, and I don’t mean to knock that, but I just can’t guarantee that I would. Or if I did, I think there would possibly be an element of projection. I think my experience, for better or for worse, is a very American experience. A very complicated American experience, but still an American experience.

So in the Fragmentina performance, basically what happens is she wakes up in this space, and she’s not sure how she got there but she has this feeling that it wasn’t really her choice to be there. There are all of these objects around, and some of them look vaguely familiar but she’s not sure how to relate to them or what they mean in relation to her history. So she starts to piece together these little assemblages just based on her instincts. For me that was a reference to how people who are the descendants of slaves have kind of created their own culture, from whatever they can remember of Africa and also whatever they’ve taken in from European culture. Christianity plays a big part in that. I wasn’t raised religious so I wasn’t so keen on using the religious imagery in the work, but I think if you read that history, the church has a huge role, especially in the creation of African American music. So she’s in this space and she’s piecing together this identity based on whatever is around her. She decides that she’s going to try and find her home, so she starts to build this ship, but it doesn’t really work out for her. She ends up going back to the shore and decides reluctantly that this is her home. At the end she’s waving this American flag very methodically. As she’s doing that, her facial expression becomes this very gritted teeth smile. This embrace of patriotism and nationalism simply because that’s all we know is really interesting to me. We have such a loaded history of violence and oppression, but it’s the only identity that I really know. I don’t consider myself a patriot at all, but I think it would be a falsehood to deny that I’m American.

I mean nationalism is the root of so much violence and oppression throughout history.

At the same time though I do think that there’s a reason why people want to celebrate where they’re from. I think black culture can be like that too. A lot of the creative expression that has come out of African American life is very much about pride. People can get almost dogmatic about it. It comes from a place of being displaced from one’s origin, so there’s a need to continue to foster and support community. I’m someone who really believes in supporting black culture and black artists, but I do think that people can get to a place of zealotry about the codes and the ways in which people carry themselves in terms of blackness. You see a lot of instances of people saying that you’re “not black enough.” There is a degree to which I kind of agree with that––like Ben Carson could have his black card revoked. He’s doing work that actively hurts black people. But discrediting someone because they listen to the “wrong” kind of music, or talk a certain way is absurd to me. I think it’s this defensiveness that comes from a fear or erasure and erosion of a culture. The reality of it is that we’re forced to be in this place and live here and adapt to whatever is around us. There’s going to be all kinds of different experiences of that. The more important thing is just keeping people happy, safe, healthy, and out of the clutches of the state. At moments my “blackness” has been attacked. When I was a kid it was really painful, but now I can understand that a lot of people are just dogged by the system and have learned to be suspicious of people in order to survive. I’m not someone who has passing privileges in terms of appearance, but I am someone who, because of my upbringing, can navigate certain spaces more easily. I recognize that a lot of people, due to factors that are completely out of their control, aren’t able to do that. I’ve just become very aware of the mechanisms that people use to defend themselves in the face of things like that, and I think that people can become very antagonistic from always having to defend themselves. I myself experience a ton of casual racism in white, supposedly progressive spaces, and it makes me feel unsafe. When my awareness of that is heightened, I also feel confrontational. We have to acknowledge these feelings and the dynamics that got us here, but I also don’t think it helps the black community to always be arguing over whose blackness is more authentic. I think white supremacy wins when black people put energy into tearing eachother down.

What is your experience when you’re performing? Do you go into this space where you become your character, or are you very aware of what’s going on?

It’s hard to say, I was reading a lot about what distinguishes performance art from theater, and I think that one of the main distinctions is that when you’re performing it’s not as a character, it’s as you. But I do think that this piece is a hybrid between performance art and theater. I mean, Fragmentina is definitely an embodiment of a lot of things that I’ve experienced. So I think I kind of go in and out of being myself and being Fragmentina.

There’s this sense of discovery and bewilderment in the work, and it’s hard to authentically have that when I know what all of these objects are and I know what’s coming next. So you do kind of have to act for this specific piece. There are some performances where I’m not necessarily going into the headspace of a character, but I think that this particular performance was unique.

At the performance, it was mostly white people, but there were a few black women in the audience. I would really like to do this piece in a space where there are even more black women, because I think that’s really who would relate to the piece the most. I’d be curious to see what the impressions were from everyone there about what they thought about the piece. I think black women would have a heightened understanding of the work.

Did you speak to people after the performance about it?

A little bit, but I didn’t really get too in depth. There was one gentleman who really liked the piece and he had this feedback that I should have had better lighting (laughs) which I understand, but in terms of content I didn’t really have too many conversations with people about it. I think in the future I would love to travel with this piece to more black spaces and hold Q and A’s after the performance. A big part of my work is this idea of the ocean, it’s something that’s always interested me. A lot of black communities are historically next to the ocean, and in terms of black spirituality, the sea has a big significance. It would be amazing to do a tour of predominantly black sea-side communities and talk to people about how they read the work. I’m sure I’d get a pretty wide range of perspectives. I think in general there needs to be more dialogue around performance, because it’s so ephemeral. Also the immediate effects of a performance can be more intense than a lot of art experiences. Performance is so visceral and intense and personal and it seems weird to have this intense experience and then just everyone leaves and no one talks about it again. That’s something that I would really like to cultivate. I think in the art world there can often be this stigma of performance as a side-note, like a performance at a gallery show. Sometimes this can be really cool, but often performance is treated as this peripheral spectacle. There’s a lot of room for theory and discussion.

Will you explore this character again?

I do want to revisit this material. I’m applying to residencies right now with it and am trying to figure out other places to perform it at. I don’t have anything coming up in the next few months but I’d really like to revisit it in the coming year. I think there are a lot of avenues that this story can take so I’d like to see what other things I can do with it. She’s a really good character for me to talk about things that are constantly on my mind through. I have no intention of letting her go. I mean performance is always ephemeral in nature. This performance was just 15 minutes but I would love to try and do a more durational piece, maybe as an installation. I think that I could really go wild if I had more resources and time.