Interview: Jillian Billard

Photo: Kat Slootsky

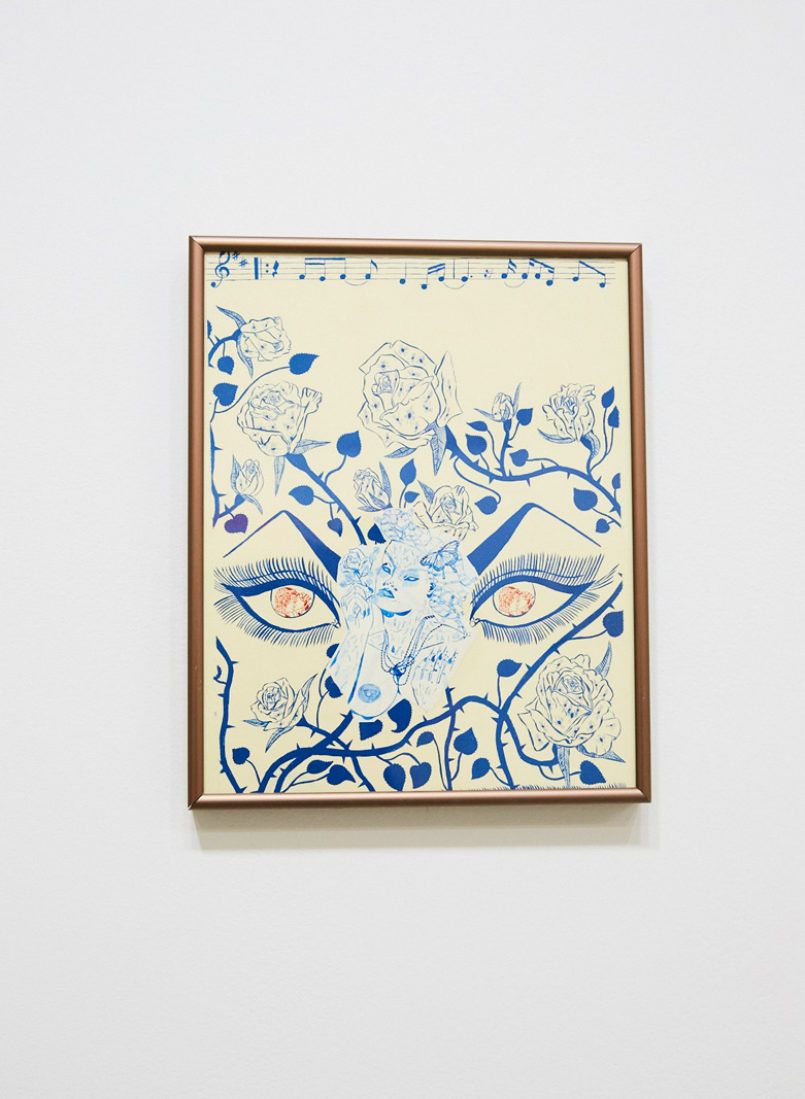

Reoccurring dreams of romance taunt the half-human, half-animal figures in artist Heather Benjamin’s newest series Death of a Tail, now on view at Bushwick gallery Dress Shop. The revelatory collection of works features sphinx women languidly dismembering themselves; women with Medusa-like coils of hair physically distraught by their incessant memories and recurring traumas; and writhing, secreting bodies amidst landscapes dotted with broken mirrors, bloodied roses, and winged insects. To me, Benjamin’s work has always felt reminiscent of Japanese erotic art from the 1600s-1800s, specifically the works of artists Katsushika Hokusai and Kitagawa Utamoro. Much like these works, Benjamin’s newest series of work is riddled with symbolism, and seems to resonate deeper within the human psyche than the realm of language can convey.

A central figure of contemporary DIY/zine culture, the Providence-based artist’s evocative black linework drawings have long been intrinsically associated with their physical book form; and have often been regarded as artist’s books or comics. Benjamin’s newest works in Death of a Tail defy categorization; and appears not so much a departure from her earlier work, but rather as a deeper exploration. Moving from the zine format into larger scale paintings and drawings that stand alone as singular objects offers an iteration of the artist’s work that indicates that her works have never meant to be read cover-to-cover. Here Benjamin experiments with a broader palette of colors, scales, and mediums. The renewed context of the artist’s meticulously detailed works grants them breathing room, and invites the viewer to sit and meditate on each work a bit longer.

Benjamin’s half-human, half-animal figures present a variation on a theme, portraying similar sentiments to her earlier series of works such as Sad Sex and Romantic Story. The animal figures seem to tap deeper into the traumas of existing in a woman’s body; specifically addressing notions of sexuality, intimacy, self-perception, body dysmorphia and trauma. What makes Benjamin’s works so visceral is the dichotomy between supposed opposites. Her subjects are at once strong, fierce and self-assured, while simultaneously visibly physically weary with emotional grief. The self-mutilation alludes to a shedding of some external, tangible aspect of their pain in order to resist succumbing to its grasp. Whilst grotesque, the works are simultaneously beautiful, and depict a cathartic reconciling with the self.

We had the pleasure of speaking with Benjamin about her inspiration for the works in Death of a Tail; how exploring new mediums has changed her practice; and the cathartic release of creation.

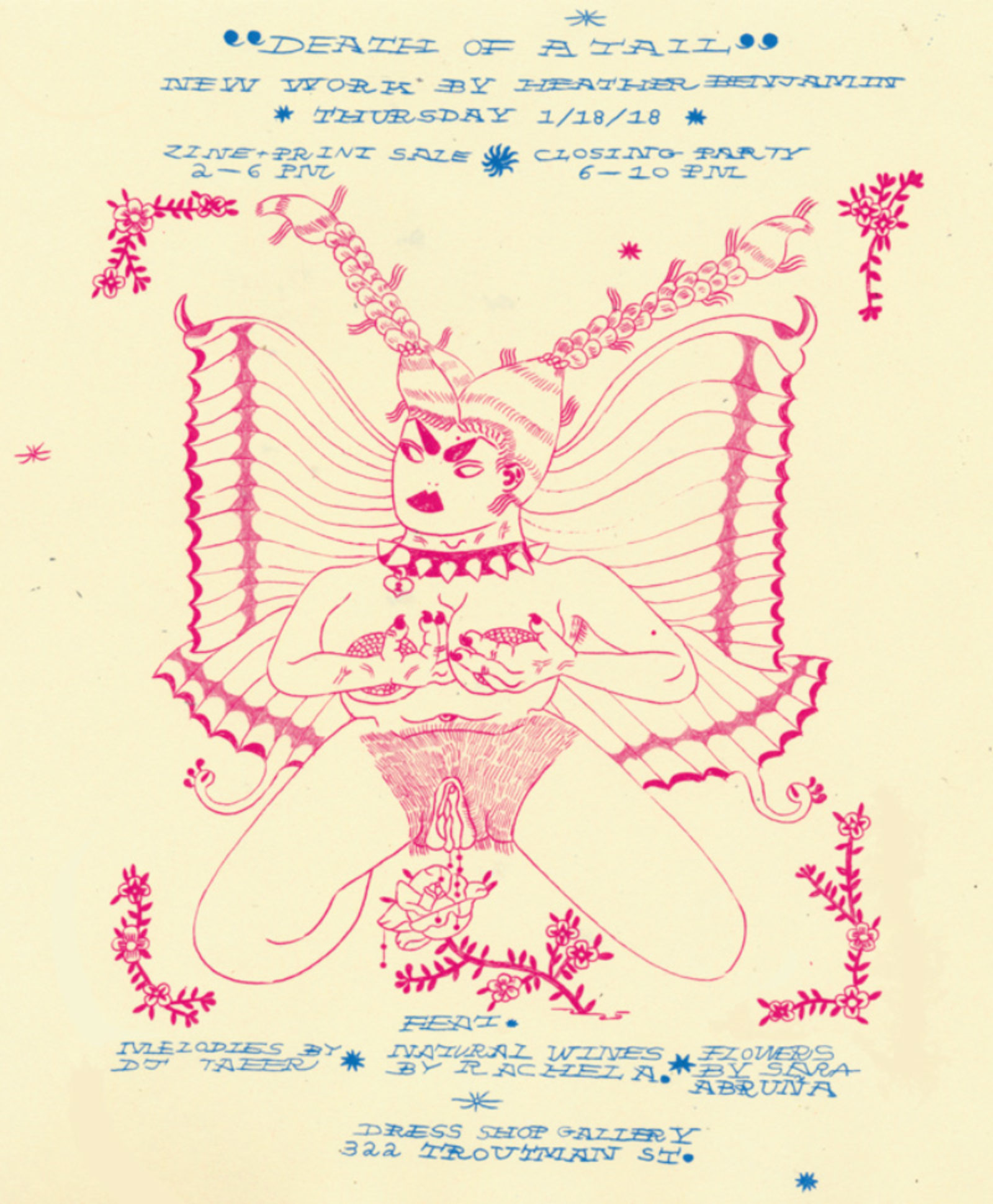

((Death of a Tail is on view by appointment until Thursday, January 18 at Dress Shop Gallery. A closing reception will take place on January 18. Flier below!))

You have long been an icon of the DIY/zine community, and your illustrations and publications have been widely reproduced and distributed. How are the paintings and drawings in your most recent show, Death of a Tail, a departure from your earlier work?

DIY/zine culture, printmaking, and self-publishing are always going to be fundamental to my practice. But over the past few years, I’ve found myself wanting to expand the way I work. It wasn’t that I was interested in departing from these practices completely; but I was beginning to make images that are not necessarily destined for reproduction for the first time. I wanted to make works that are meant to stand alone as singular drawings or paintings, and that are most effectively viewed in person. This is really the polar opposite of how I’ve worked for a long time.

Until a few years ago, most of my work was created with the intention of reproduction, so the original pieces didn’t even make sense to me in a lot of cases. In the past couple of years, I’ve started to open that up a bit, and have been making drawings and paintings on paper that still met the criteria that allowed them to be photocopied or assembled into zines (i.e. still the right size to fit on a photocopy bed, on light backgrounds, and only using one or two colors). They could be framed and hung as original works, but could be printed well, too. Now I’m trying to open up even further by working on a much larger scale, using paint on canvas and paper. It’s refreshing and exciting for me to be working that way, because it opens up so many different possibilities for my work.

I liked the way I worked before, but it was starting to feel a bit restrictive. Now that I can layer; paint over things; have endless palette options; and am not taking the specifications of a photocopy machine into consideration every time I conceptualize a piece; there’s a lot more that I can do. It’s simultaneously really exciting and a little overwhelming. In Death of a Tail, I’m showing some smaller works on paper that I made during my transitional period from making strictly photocopy-able work to making non photocopy-able work, which are these ink and gouache paintings on paper. When I started making them, I thought, ‘I’m working large scale now! This doesn’t even fit on a photocopy bed, this is so crazy and new!’ Then I would step back and realize that they’re still only like, 18 x 18 inches or something. Not huge. That’s how tiny I worked for so long—anything over 8.5 x 11 seemed insane. So in the show there is some of that stuff, and then there’s my first sort of expedition into breaking out of that, which are these works in acrylic on canvas that I made over the last several months. Two of them are sort of mid size, 34 x 34, which felt somewhat manageable to me, and three of them are huge—like 5.5 feet tall and 4.5 wide I think. Those were an insane thing for me to jump right into from working so small. It was emotional and hard, but I think that was the only way I could have made that transition; just totally headfirst.

How do you find that the works speak differently in book form, as a series of works, versus as distinctive objects?

I don’t know if it’s the same for other artists, but I’ve noticed that people’s perception of my work has been very influenced by the fact that I’ve self-published so many books and zines of my drawings. For years I have been referred to as a cartoonist, and my publications of drawings have often been regarded as comics. I think talking about what can constitute a comic is an interesting conversation in itself (that is too long for me to try to get into here), but, at the risk of making a big generalization, I would say that my drawings have never really been comics, at least not in a conventional sense. I don’t use word bubbles or write dialogue or create linear narratives. (Not that all comics necessarily have to abide by those parameters, there are so many different kinds). But even when I was making little groups of drawings for a zine, like the three or four drawings that would comprise one fold-out issue of Sad Sex, I wasn’t thinking too much about a linear narrative. It was more of a related group of images.

I’ve always thought of my self-published works as “books of drawings,” which probably speaks to the fact that I was really trying to reconcile having people pay attention to the singular images while they still existed in this book format, rather than viewing the individual works only in the context of what existed around them. I think that because I published images in sequence, on pages that were being turned by the viewer’s hand, my work has been viewed as sequential, with the images being read left to right or front to back in a book, which incites a narrative in the viewer’s head. Sometimes it’s a narrative that I hadn’t intended, or even known that I intended.

I think that the works speak differently grouped together in book format because of this sort of human, and also Western impulse, to read things from beginning to end and make sense of them. The book of drawings called Romantic Story I published a few years ago had no concrete narrative or storyline. To me, all of the images were singular, but related. They were less of points on a timeline and more just like points floating in space. Of course I did take into consideration how I organized the drawings within the book, and which ones I chose to start and end with, but not in the sense of deciding ‘here’s where this story begins, and here’s where it ends.’ Some of my considerations had to do with creating a feeling and understanding of what I was thinking about with the works as you flip the pages, but some of the choices I made in arranging them were purely based on aesthetics.

I’ve talked to a lot of people who not only expressed that they see a clear narrative in that Romantic Story, but have also literally referred to it as a comic book. I think it purely has to do with the way that the format makes people contextualize the drawings. When I’ve displayed a print or an original of one of the same images on a wall, it’s not like anyone goes up to the work and says, ‘oh, she framed a panel from her comic book.’ In that context, it’s just a singular image. One of the reasons I love the book format is because it encourages viewers to seek their own ideas about the relationships between images by considering them both as singular images, and as a publication as a whole. But sometimes I wonder if, working in the book format, the in-depth probing of a singular image becomes a bit harder, either because of scale or because it’s being drowned out by the larger body of work.

Displaying the works as distinctive objects provides more of an opportunity for further excavation of the world of a singular drawing or painting. There’s less of a time limit as well; without the urge to turn the page, you can just sit with it and be in that one moment. I honestly love both singular and serial formats, and I’ll always make both. I think I’m just trying to seek more of a balance between the two in my practice as a whole, and see what the latter can do for my imagery, having focused on the book format for so long. But I will always make books.

It was emotional and hard, but I think that was the only way I could have made that transition; just totally headfirst.

What is the symbolism of the title Death of a Tail?

I had some dreams last year in which I had a tail, and would cut it off. Some friends told me that they too had been having dreams involving tails; sometimes they were cutting them off of animals, or had one themselves. So I was reading about the symbolism of tails on some hokey dream interpretation websites, which led me to read about the biblical symbolism of tails and the symbolism of tails in literature. I was interested in all of the ways that people have interpreted this body part that humans don’t have. I had also already been working with imagery of half-animal, half-human tailed creatures such as the sphinx over the past couple of years. My work is very diaristic and autobiographical, and the women and creatures I draw are often ways to articulate different aspects of myself. So I started drawing this dream I’d been having, and actualizing it through my characters.

There are a lot of different ways that people have historically conceptualized tails. I became interested in the idea that it can symbolize one’s sexuality, freedom, animalistic side, and wildness. That seemed to correlate with the dreams I was having, and where I’ve been in my personal life over the past year or so; feeling a bit disconnected with my spiritual self and my body in ways that have made me feel less like a sexual being; less wild than I used to feel. I thought that perhaps that’s why I was having those dreams—and I felt like it was a poignant metaphor. It lined up in this way that allowed me to make work that felt relevant and accurate to my current experience. I started coming up with all of these sad visions of sphinxes alone in the desert snipping their tails off wistfully. It made me feel better in a weird way; I see those creatures as myself but also as my friends in some sense, or as my sisters, so I felt a little less alone having them go through it too. Even though the loss of a tail is really somber and upsetting, I was trying to create images where the experience made it also feel beautiful and feminine and true.

What has been your primary medium of choice for the works in Death of a Tail? How has this shift in medium, color, scale, and increased negative space changed the way you approach your process?

Pretty much all of the work in Death of a Tail was made in 2017. The majority of the paintings are ink and gouache on paper. The biggest thing that changed about my process with these works is that I completely stopped pencilling things before inking them. I used to make works on paper in more of a traditionally illustrative way, where I would do some sketches, then pencil it out, then ink on top, then go back and erase the pencil, and then do final touch ups in ink. In early 2017, I started just going straight to brush and ink. I enjoy figuring things out as I go along with the brush so much more. It’s more thrilling and intense for me. I also think that the works have become more interesting visually, since fluctuations in proportions and composition happen in the moment, due to less initial planning. For illustration jobs and freelance stuff, I will still pencil things out in a more deliberate way, but with my personal work, I have really come to prefer just having a general idea of where I’m going and seeing how it evolves.

The other big departure point for my work in this show is the addition of painting on canvas to my practice, which is something I had not experimented with on this level until this year. This has definitely changed my process in a lot of ways: not working on such a tiny scale anymore, not sitting at a desk, not exclusively using the tiniest brushes, and having the freedom to paint over and layer things instead of dealing with how unforgiving using ink on thin paper is. There is more room for things to evolve and change within a piece. I also realized that the approach I now take to working on paper, where I thumbnail and just go for it, is a little less forgiving when working very large scale. I still don’t totally want to pencil things out, but having a clearer idea of what elements will be placed where is helpful when working large scale, which is something I’m learning. Also, now that my options for my palette are basically infinite, whereas before I was somewhat restricted to whatever inks the thin papers I like to paint on could hold, I’m learning how to strike a balance of planning and improvisation with color choices, too. It’s really exciting to me.

There is often a common narrative thread or theme throughout your works. When did you first develop the distinctive style that you work in today?

I was at my parents’ house for the holidays, and looked through some boxes of old artwork from high school. I found drawings that I made when I was 16 and 17, and was struck by how they looked like precursors to the linear style that I have been working in as an adult. I think I have always been drawn to linework. When I was 18 in my first year at RISD, taking foundation year classes and often being required to make work that wasn’t stylized, I was keeping sketchbooks full of the drawings I actually wanted to make; all of which were super linear and dealt with sexuality, and were honestly pretty emo, for lack of a better word. I think that was around when the style I work in now started actually taking shape. I made the first two issues of Sad People Sex for a zine-making mini class I took over Winter-session my freshman year, and that was the first time I collected and published some like, black linework hairy drippy people fucking. So I guess that’s a good marking point of when I started making stuff like what I make now. The way I make my work, and my mark-making itself has changed a lot over the past ten years, but I think it’s all kind of stemmed from that time when I was 17 or 18, when I was filling sketchbooks with figurative line drawings. I wish I still had those books—they were all these thin moleskine notebooks, the largest size, that I had hand sewn together. So instead of being a 40-page sketchbook, I had this probably 200-page one. I left it in a Bank of America in Providence when I was 19 and took the bus back to my dorm. When I realized I didn’t have it, I freaked out and took the bus back, but it was already gone. That still hurts to think about—it was basically all of the diaristic drawings and writing I made from age 17 to 19. It was such a huge loss. I think there would be a lot of weird evidence and foreshadowing of my current work in that book if I could take a look at it now.

How has being a part of the punk community influenced your style, or allowed it to evolve?

There are a lot of reasons why growing up invested in punk and DIY culture has made my work the way it is. I think one of the reasons why I was comfortable at a fairly young age with making and showing really personal work was because most of my media intake was subversive or intense forms of art and music. I never thought twice about my work being graphic or intimate. I think part of that is just my personality, but part of it is becoming comfortable with different forms of expression that verge on the more ‘extreme’ end of the spectrum, simply because that’s what I was into and what I was involved in.

I grew up looking at artists like Raymond Pettibon, whose work I found through Black Flag, not the other way around. He was probably the first artist I knew of who made stark black and white linework imagery that functioned as singular pieces, but also existed in zine format. The first zines I ever saw weren’t art books or comics, but punk rock zines at friends’ houses in New Jersey, about like, how to DIY an abortion with herbs, or stories about hitchhiking and riding trains. Some of the first ones I was exposed to were local, personal zines made by people who just wanted to get their writing out there or spread information pre being able to google search everything—not that this was SO long ago, probably around 2006, but even just that recently there weren’t a ton of websites where you could find out how to make fire cider or read about tall bikes or some like that.

I also saw stuff like individual issues of Cometbus early on, and even though I wasn’t interested in writing personally, that was the first time I started thinking about zines as a way to cheaply and effectively disseminate not just helpful information, but a creative output to a larger audience. That’s how I started thinking about making zines of drawings. I didn’t actually see people making booklets of drawings until I discovered Printed Matter when I was 17 or 18. I interned there discovered their amazing collection of handmade booklets of photos and drawings and zines from artists all over the world and realized, ‘oh, people are already doing that!’

Honestly, I just keep thinking of more ways that punk made my work the way it is—photocopying is a big one I take for granted. Not only was that obviously the way to go with trying to make your own zine, but I also made lots of flyers for shows in New Jersey and New York, and got really into the routine of making work that would reproduce well. I became really well acquainted with photocopiers, and used what I learned from those experiences to print my work. I guess it’s really intrinsic to my work in more ways than I realize before I started answering this question!

I started drawing half-woman, half-animal figures a few years ago. To me it was a natural progression for my characters, and it helped me convey my experience of womanhood symbolically; feelings of being untethered, wild, connected to nature, ravenous, sexual, and in captivity.

Each element and detail of your works feels incredibly deliberate and calculated. One element I love from your most recent works is the link between bodily secretions, mapping, and constellations. Can you talk a bit about how you come to these common threads of detail within a series?

This is something that is almost subconscious to me; I hardly know where to start with trying to describe it, which is interesting to me. I’m not sure how deciding where to place those details comes to me—it feels extremely organic and natural when I’m doing it, and I’ve definitely never planned out where those little bits are going to go beforehand. I usually plan where larger elements will be, at least in a vague sense, but all of those embellishments come at the end. Choosing where to place a tiny star in a field of negative space is this really luscious experience of creating this thing; it feels random but also totally calculated. I do obsess about them if I get them wrong. If I draw a few stars or a few drips in the wrong place after having worked on a piece for a very long time, it can totally ruin a piece. When I work on paper, it’s so hard to fix. In the paintings now, it’s a lot easier—I can just paint over it until I get it right. I don’t mean to say that what you’re referring to isn’t deliberate, though, the placement is just random and unplanned until the moment it happens, and at that point it’s mostly guided by intuition. It definitely is deliberate, to have this top layer that happens after all the other larger elements of the piece are done; where I’ll add all of these tiny bits—the stars, the drips, little bugs, bits of noise. It ties the piece together for me, and it’s this crucial final step that I can’t avoid. The decision of which elements and how many of them to include from this vocabulary of tiny symbols usually comes from a combination of what thematically makes sense in a particular piece, but also the aesthetic consideration of needing to balance out a composition. Sometimes I’m adding those bits at the end just to make everything feel more even from a visual standpoint.

In the press release from The Dress Shop, it refers to the characters in your work as avatars. Do you see your drawings/paintings as self-portraits? Is creating a cathartic process for you? How does the process of externalizing grief help to heal the traumas of existing in a woman’s body?

Yes, I see all of the protagonists of my drawings as symbolic of aspects of myself and my experience of being a woman. They are all self-portraits, though not all complete ones—sometimes they just represent one facet of myself. I love the phrase you used, ‘externalizing grief’—I think that is a perfect description of what I do in my work. I’m not sure how I would reconcile the personal traumas of my life and the traumas of existing in a woman’s body without having a regular practice of making art. The time I spend making my work is heavily introspective, specifically with respect to my experiences as a human woman. It helps to look back on a finished piece; to see this visual representation of pain, abjection, grief, trauma, that has managed (at least when I think I’ve been successful in the work) to create some beauty and/or articulation from experiences that, if they live only in my head, can feel impenetrable, inexplicable, and overwhelming. The most helpful aspect of my work is sharing them with other women, or anyone who can relate to the feelings I’m expressing, and conversing about them. The works serve as catalysts for relating to others who share similar traumas. It is so fulfilling when other people respond emotionally to the work, and in turn feel understood and less alone. It makes me feel that way too.

Your work deals with primal emotion. (I remember opening Sad Sex for the first time and feeling completely floored, like I was tapping into some deeper understanding of my own psyche…it’s simultaneously aesthetically beautiful and manic.) How do abjection and extreme polarities play into your work?

This is the area where my work is the most personal and diaristic. I feel that way about myself and my life—I am constantly fluctuating between extreme highs and lows. This is sort of just how I’ve always been. It changes somewhat based on the phases of my life that I’m moving through, but in general I have always been a high strung, sensitive, hyper-emotional person. I have self-confidence and I have self-hatred. Like many people! In my work, I have mostly wrestled with the darker side—it’s rare that I have made work about feeling pure joy or contentedness. A big part of why I make my work is to sift through my mental state at the time I’m making the piece, and to try to make sense of and come to terms with pieces of myself. I will take these dark or upsetting feelings and try to draw them in order to hash them out. Through the process of drawing, I also try to make them somewhat beautiful and interesting, in order to constantly remind myself that it’s okay; it’s not the end of the world. I draw to remind myself that this experience can be viewed as gorgeous and human if I can take a step back from it; processing each detail and practicing detachment. I’m trying to convey my experience and my inner monologue at its worst, with some sense of wonder and humanity and beauty. It does help me to realize and notice deeper things about myself. I hope it can do that for other people too.

How did you become interested in fusing the figures of woman and animal in Death of a Tail? What is the symbolism of the Sphinx and Medusa figures, and what drew you to them?

I started drawing half woman, half animal figures a few years ago. To me it was a natural progression for my characters, and it helped me convey my experience of womanhood symbolically; feelings of being untethered, wild, connected to nature, ravenous, sexual, and captured. It became a useful metaphor for me. Depending on the animal that she’s mixed with (or sometimes the combination of animals), it can help me express different ideas. The sphinx is regal, worshipped, and solitary. The snake is historically evil, (or at least perceived that way), sensuous, but also overwhelmingly phallic. Recently I’ve gotten really into drawing dog ladies, which has let me play with ideas of being smart and wild and energetic, yet easily captured and possessed and obedient. Man’s best friend.

Who are some artists or illustrators that have been/are influential to you?

I think the ones that have carried with me the longest are Leonor Fini, Virgil Finlay, Henry Darger, and Suehiro Maruo.

What does a typical day look like for you?

Usually get up around 8:30, stretch for about a half hour and have coffee and breakfast, try to get my emails in order, then head to the studio for the rest of the day. I’ve been trying to get in there earlier, because the building where my new(ish) studio space is also rents a lot of rooms to bands, and everyone starts showing up for band practice around like, 6pm, at which point it gets pretty loud. So I like to get out of there by then and either go to yoga or come home and make dinner—cooking is a super effective decompression activity for me and I do it often. For the rest of the night, I usually spend time researching things related to work or plan out drawing ideas, stuff like that.

Who are you listening to right now?

Literally at this moment I am listening to the Sun Ra album Sleeping Beauty which has been on heavy rotation for me lately along with Boards of Canada and Bohren & Der Club Of Gore—all of which have been really chill wintery music for me recently, and all good to work and think to.