Images courtesy of EXILE Books

Photo by Sarah MK Moody

Text and interview by Monica Uszerowicz

In the introduction to their book Fairy Tales: When Architecture Tells A Story, Matthew Hoffman and Francesca Giuliana-Hoffman, founders of Blank Space—an online platform for media—write: “Fairy tales might seem like a foreign topic for the architecture community—but at their core is the power of communication. Fairy tales are relatable, yet sophisticated and nuanced, just like great architecture.” Fairy Tales is the result of a Blank Space competition that challenged architects to write and design an “architecture fairy tale.” The idea here, of course, is that architecture is complicated, communicative, and even experiential—it can inspire a great many feelings, if done well, or, under other circumstances, none at all. It’s worth keeping in mind, too, that all bodies experience architecture uniquely—moving through a space is only a small part of establishing a physical connection. There is also the ability to see it, to smell it, to touch it, to feel it.

It was with similar ideas in mind that EXILE Books—a Miami-based artist’s bookstore-installation hybrid—and the Miami Center for Architecture and Design (MCAD) collaborated to showcase LISTEN TO THIS BUILDING, an architectural exhibition for the blind and visually impaired—and for all those who wish to engage with a building in a new way. Opening on September 3, the exhibition will turn ten downtown Miami buildings into newly touchable, living pieces of multimedia, all sitting at a metaphorical intersection of Miami history, architectural exploration, and, most profoundly, accessibility.

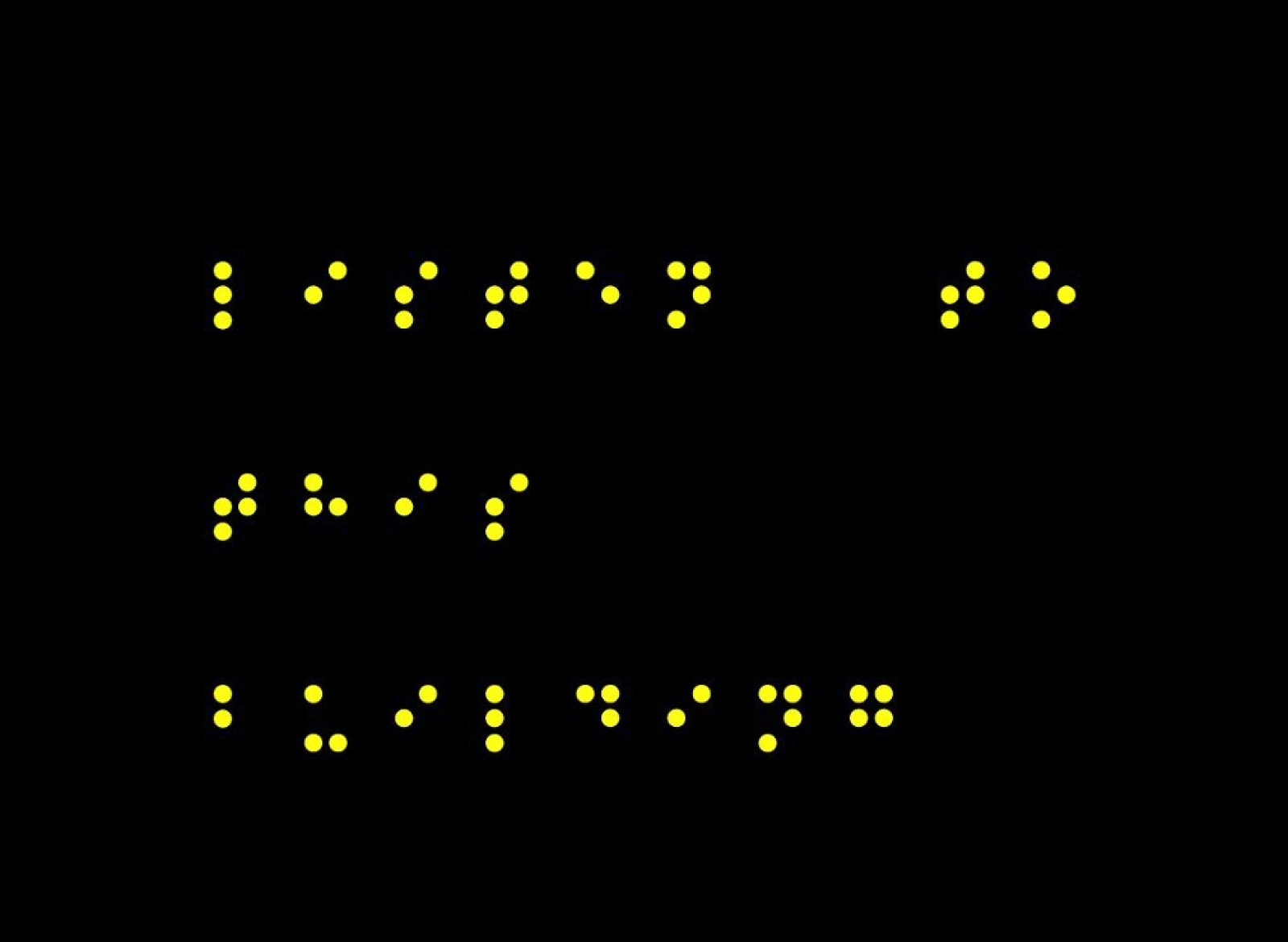

Fittingly, the showcase coincides with the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, and contains several components: an outdoor audio piece on the front steps of MCAD, featuring stories about the building in which organization is housed—the Old U.S. Office and Courthouse—and others in the neighborhood; tactile relief works of downtown buildings with braille text inside MCAD’s gallery; models of downtown buildings, designed by students from Florida International University’s College of Architecture + the Arts utilizing 3-D printing, then covered with boxes so that viewers must touch them to “see” them; and, finally, a book, published by EXILE, containing tactile reliefs of the buildings and transcriptions of the aforementioned stories, all transcribed in braille.

In addition, LISTEN TO THIS BUILDING will host a few moving parts during the exhibition, among them a blindfolded Orientation and Mobility Tours of the Old U.S. Post Office and Courthouse—in partnership with Miami Lighthouse for the Blind—and a series of events designed to instigate public engagement on issues of accessibility, art, and architecture. The expression of history and the arts—particularly a marriage thereof—to those without access is a feat both creatively experimental and ultimately altruistic. Indeed, LISTEN TO THIS BUILDING might be the first exhibition of its kind. Says Ricardo Mor, Operations and Programs Coordinator of MCAD, “I approached EXILE the second I started at the center. I love their work—everything they do is informed by whatever space they’re in. Architecture shows, in general, follow a certain format; we wanted to sort of evolve the language of what an architecture show could be.” After considering a sound installation inspired by Bruce Nauman’s Days, “we interviewed people who had a connection to the buildings we’re showcasing, and asked them to describe the building to someone who cannot see. We realized very quickly that language fails people who are blind or visually impaired.” Mor adds: “There is a genuine appreciation of evolving architecture here, and of reaching out to an audience that’s underserved in the art community in general.”

In light of such a transformative experience, we spoke to EXILE Books founder and former Printed Matter manager, Amanda Keeley, about LISTEN TO THIS BUILDING’s development and fruition. Her ideas are as thoughtful, sensitive, and unique as the project itself.

Accessibility is something I’ve thought about often in regards to Miami’s creative community (and to the “art world” in general)—how it can be expanded in a way that’s compassionate and inclusive. What sorts of questions were being asked that led to the development of this exhibition?

Whenever EXILE Books travels to a new location, we try to explore fresh territory, seeking to transform and activate the space and to create a new experience for the audience. EXILE focuses on artist’s books, which is often presented as a range of materials which are accessible and can reach a broad audience. The nature of EXILE is to be experimental and to evolve with every location, in a way that is inclusionary for all communities. When contemplating a new installation at the Miami Center for Architecture and Design, how could we continue to expand our engagement in a way that reflects the experimental business model of EXILE? How could we alter how architecture and this location is experienced? This idea was at the root of what we were mulling over during the beginning stages of LISTEN TO THIS BUILDING’S development.

I was astonished when I started to think about accessibility of design and architecture, particularly regarding individuals who are blind, but also the processes of how people formulate a sense of place. During our initial meeting with Miami Lighthouse for the Blind, we learned about how someone who is blind encounters an unfamiliar space and the obstacles one may experience, but also the amount of sensory sensitivity: physical awareness, the acoustics, the tactile attributes absorbed that I would normally overlook. By removing the visual cues of MCAD’s interior, I had an entirely altered understanding of how information can be received and processed. I decided to shift the paradigms of a traditional architectural exhibition and remove all visual stimulation, thus reinforcing the idea this exhibition would privilege those who are blind or visually impaired.

Accessibility is inherently about privilege, defined by the barriers of power and control, to limit how people experience something or what is shared or communicated. By shifting the dynamic to be inclusionary, rather than exclusionary, I hope LISTEN TO THIS BUILDING will change how we experience an environment and will open up dialog for how communities can be sensitive and improve upon accessibility for all.